For last several weeks I've been exploring SYCL DPC++, which is an open standard for expressing accelerated computing logic, targetting CPUs, GPUs, FPGAs etc. I find it easier to work with than Vulkan Compute, due to Vulkan requiring me to specify almost every single fine grained detail regarding how to perform accelerated computation on GPGPU. Here using SYCL DPC++, I enjoy quite a great level of flexibility in detailing, letting me specify details only when required. This week I decided to implement root finding algorithm using SYCL DPC++, where I try to approximate root of single variable non-linear equations like 👇

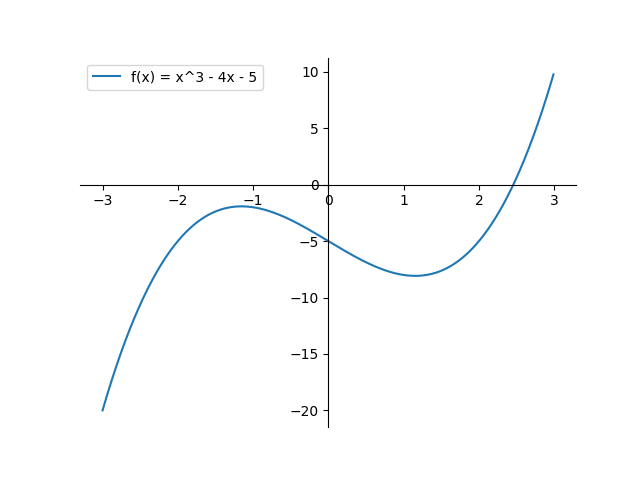

I choose to go with standard way of doing it --- Bisection Method. First I implement sequential form, then I implement SIMD parallel model of it using SYCL DPC++. I choose to work with f(x) = x ** 3 - 4 * x - 5 throughout this document. I begin by plotting aforementioned equation.

Assume a, b are two values for which f(x) has opposite signs.

So f(a) * f(b) < 0. Input z for which f(x)

produces 0, must be living in (a, b) interval. For finding where exactly z lies

( read with better precision ), I split (a, b) interval into two equal halves & try to evaluate f(x) at m = (a + b) / 2.

If it turns out that f(a) & f(m) has opposite signs ( read f(a) * f(m) < 0),

clearly z lies in interval (a, m). If not, then z must be in interval (m, b).

I keep following same logic flow in updated interval, until I discover some (a, b) which has acceptable

level of difference ( read |b - a| ). Let me also define, I'm open to accept |b-a| < 10-5.

As soon as bisection method reaches this level of approximation, I terminate algorithm.

Bisection method simply says 👇

I want to step through this algorithm, where I input a = -3, b = 3 & c = 10-5. I evaluate f(x) at a, b obtaining 👇, which clearly says root must be in (-3, 3) interval.

Evaluating f(x) at m = (-3 + 3) / 2 = 0, results in -5. I see f(a) * f(m) < 0

evaluates to false, it's clear z must lie in interval (m, b) = (0, 3). In next iteration

(a, b) = (0, 3) so m = 1.5. Evaluating f(0) * f(1.5) = -5 * -7.625 < 0, results in negative

result, clearly z must be lying in interval (m, b) = (1.5, 3). In next iteration,

a = 1.5, b = 3, m = 2.25, evaluation of f(1.5) * f(2.25) = -7.625 * -2.609375 < 0, hints

root of equation f(x) i.e. z must be lying in inteval (2.25, 3). This way I keep trying

to decrease width of interval until it goes below 10-5.

Looking at above plot of f(x), I discover bisection method is progressing towards correct direction.

Because plot says somewhere between (2, 3) root lies & I just found myself it must be somewhere between (2.25, 3).

If I keep exploring for few more iterations I belive it must lead me to better approximated result.

Instead of manually doing, I collect runlog of bisection method implementation.

In final iteration it says root must lie in (2.4566689, 2.4566803). As evaluation of f(a) * f(m) < 0

turns out to be negative, clearly solution must be in interval (m, b), where m = (2.4566689 + 2.4566803) / 2 = 2.4566746.

Before moving to next iteration, I notice |b-a| has reached below 10-5, which denotes

I must terminate algorithm now.

Approximated root of f(x) = 2.4566746, with error 10-5.

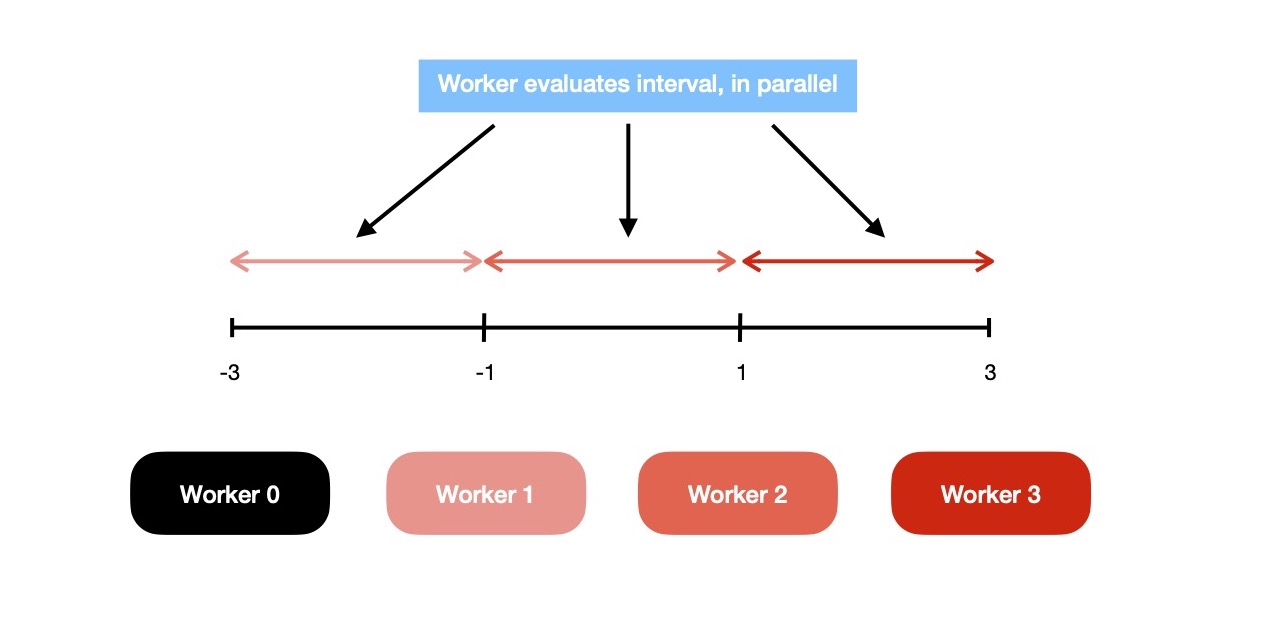

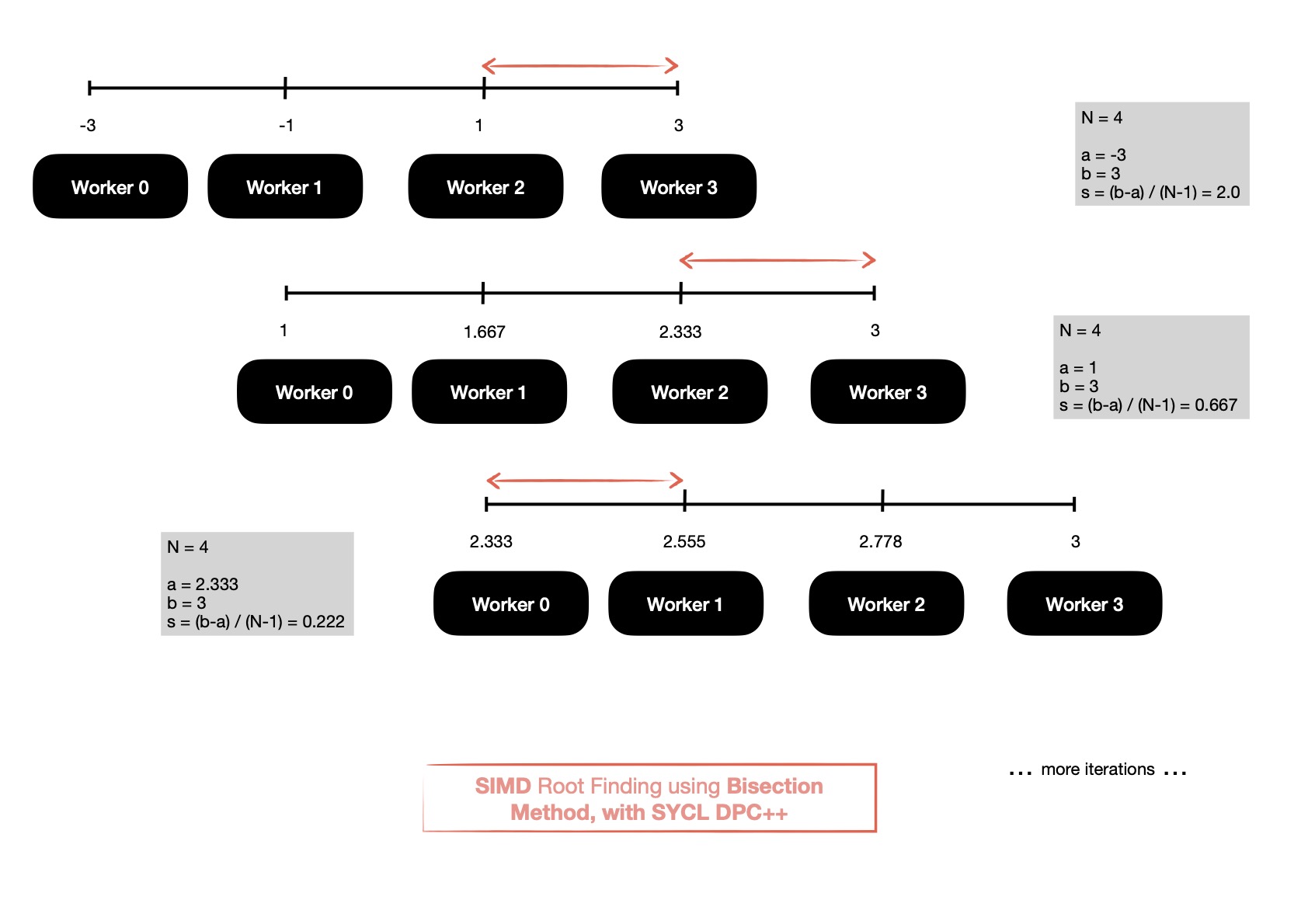

Now it's good time to implement SIMD form of bisection method. In sequential model, I was splitting an interval in half at a time; then deciding which sub-interval to select; and again iterate with new interval --- conforming to binary search style. In parallel model, instead N-workers explore whole interval (a, b) consisting of (N-1)-many sub-intervals. If (-3, 3) is current interval & 4 workers are available, it'll be splitted between them like 👇.

Each of those workers evaluate f(x) at (a + ks), where a = -3, b = 3, k = worker index ∈ {0, 1, 2, 3} & s = (b-a) / (N-1) = 2.0.

For discovering which interval to explore in next iteration, each of them evaluates f(a+ks) * f(a+(k-1)*s),

except k = 0 ( read worker_id 0 ). But notice, I've already made each of them evaluate f(x) at (a+ks)

so instead of again doing same, they'll just read it from one shared memory region which is visible to all workers.

So there's a need for synchronizing memory visibility for all workers. Because worker_3 will read

what's written by worker_2 & itself; worker_1 will read result computed by {worker_0, worker_1} etc..

Only one of them to evaluate it to true, which will update interval (a, b) for next iteration with

(a+(k-1)s, a+ks).

Let me step through the algorithm.

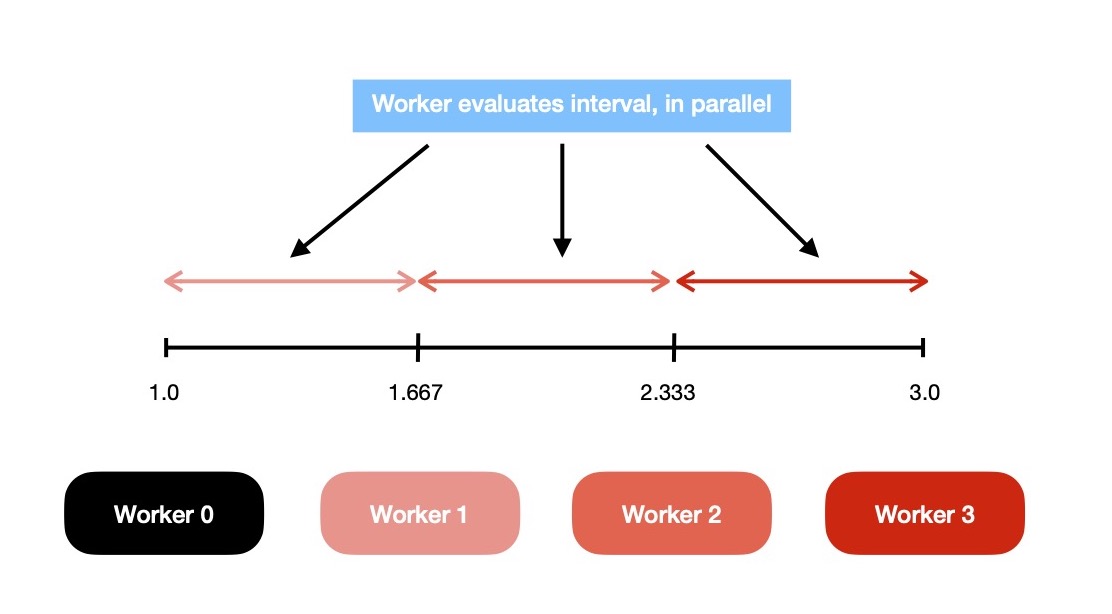

In next iteration, I again employ N(= 4) parallelly executing workers to explore interval (1, 3). Each of them works on sub-interval of width (b-a)/ (N-1) = (3-1)/ (4-1) = 2/ 3 = 0.667. Work distribution looks like 👇 now.

Each worker evaluates f(x) at (a+ks) & stores result in shared memory region, which will be explicitly made visible to all by using memory barrier.

Now worker_{1,2,3} evaluates expression f(a+ks) * f(a+(k-1)*s) < 0,

turns out worker_3 only obtains true, which hints root must be living in interval (2.333, 3).

In next iteration workers will collaboratively explore aforementioned interval. This will keep going on

until I get to discover some interval which has width < 10-5.

Though I've not yet executed parallel implementation of bisection method, I can clearly

see it's progressing towards correct direction. In sequential version, I obtained ~2.457

to be root of f(x), while parallel implementation points towards existence of root in interval

(2.333, 3). A few more interations should take me to expected value.

This is how the algorithm searches for root by splitting interval into N-1 equal sized ones which are

parallelly explored by N workers.

Parallel version of bisection method looks like 👇.

SIMD root search algorithm when implemented in DPC++ & executed on accelerator, results into 👇. I notice sequential version of this algorithm is lot faster than SIMD version, due to need for synchronization in mid of execution; before next iteration can be begun values of a, b, s needs to be copied to host & inspected/ updated. Again next iteration can be begun only when values of a, b, s are available inside kernel, which is being executed on accelerator.

My interest behind implementing bisection method using DPC++ was not to obtain

substaintial speedup, but rather understanding parallel execution model/ pattern including

ND-range, execution/ memory synchronization, memory model, data movement, work-group local shared memory,

accessors, buffers etc.

I keep both sequential & parallel implementation here for future reference.

In coming days I plan to explore SYCL specification more deeply for understanding memory model, data management, synchronization etc. in better fashion,

while implementing other parallel algorithms in DPC++. Have a great time !